With rapid innovations in communications it has been quite common for us to hear of missions of intelligence operatives into soon to be targeted territories even while these incursions are taking place. This was the case recently in the early stages of conflicts in the Middle East when we were seeing MI6 operatives on the ground identifying potential targets for air strikes. It seemed strange to me that this information was being broadcast to the world even as the operatives were engaged in their dangerous duties. I wondered at the threat that such news stories might have been to the safety of those brave men serving on foreign soil.

A day or so after recent operations in Abbottabad, Pakistan, we heard of a nearby safe house that had been the hideout for CIA operatives for several months in advance of the attack. From there these spies were able to gather intelligence observing the comings and goings in and around the building that proved to be significant.

It’s always exciting to me to wonder how these spies are able to pull off their successful missions all without being detected. They must have been seen by many of the locals so I wonder at the disguises they adopted, their skills in foreign languages and their ability to makeshift in foreign locations. Thinking about this also makes me wonder what safe houses or intelligence gathering missions are currently in operation in trouble spots around the world that could one day pay off or be busted.

It’s always exciting to me to wonder how these spies are able to pull off their successful missions all without being detected. They must have been seen by many of the locals so I wonder at the disguises they adopted, their skills in foreign languages and their ability to makeshift in foreign locations. Thinking about this also makes me wonder what safe houses or intelligence gathering missions are currently in operation in trouble spots around the world that could one day pay off or be busted.

There was a case of French “intelligence operatives” on British soil that seems to have been completely overlooked! Even though it was a fictional one there has been little or no attention given to it in 400 years, and yet millions of people have read about it in the pages of Shakespeare’s King Lear most without realizing what happened!

To many people King Lear is such a boring play! Today’s theatre-goers have a keen appetite for the loud and mournful speeches of the king “more sinned against than sinning” and performances seem to be judged by how well a lead actor does in delivering these. But there is so much more in King Lear that is so exciting that people are completely missing.

If you have been following my blog you will know that I am referring to the presence of the King of France and Cordelia on British soil. They are there disguised as a Servant/Knight and Gentleman and as Lear’s Fool.

In my earlier posts I showed good reasons for believing that France and Cordelia never left Britain, but stayed behind and served Lear attempting to direct him towards Dover where France had ordered his troops to land in the hope of restoring Lear to his throne.

How exciting is this?! A foreign king and a banished princess, France and Cordelia, gathering intelligence about movements of Queens, possible divisions between dukes, strength of military power, and trying to get those loyal to Lear, Kent and Gloucester, to help in directing the aged king towards Dover and to the safety of armed French forces. All this without being detected, for that would have been dangerous! Indeed, all of this without wanting to be even acknowledged for their bravery and service.

This is what Shakespeare has presented to us, and their cunning, covert operations have been completely overlooked for 400 years! However, the record is all there waiting to be rediscovered in the words, speech prefixes, stage directions, textual emendations, Biblical allusions, as well as evident glances at the sources of Shakespeare’s play.

I have already drawn attention to Cordelia’s getting her note to Kent whose disguise and whereabouts she could not have known unless she were the Fool. Cordelia had heard Kent’s obscure words, “He’ll shape his old course in a country new” and the Fool was there moments after Lear had failed to see through Kent’s disguise as a servant and accepted the one he had banished from the land into his personal service again.

I am maintaining that France was there too, disguised as a Servant (in the Quarto) and a Knight (in the Folio), preparing the way for the entry of the Fool by mouthing what everyone believed, that “my young lady”, Cordelia, had gone “into France”. When the Fool finally arrives on the stage for the first time, the first thing the Fool does is to chide Kent for “taking one's part that's out of favour” and then expresses the reversal of Lear’s assumed action saying of him, “this fellow has banished two of's daughters, and did the third a blessing against his will....”

Because Lear and everyone else believes that Cordelia has gone to France, she has found a way to fulfil that which she said that she would have wanted. Before leaving her sisters on the day of the division of the kingdom, she had committed her father to her sisters’ “professed bosoms”, however she wished she could “prefer him to a better place” namely her own bosom, or to what Lear referred to as “her kind nursery.” If Cordelia were in France, it would not have been “against his will.” By reversing the states of Goneril and Regan from Lear’s loving hostesses to “banished” the Fool reverses Cordelia’s state from banished to not banished and present somewhere in disguise!

There is no doubt in my mind that this shows that the Fool, Cordelia, sees through the disguise that Kent has taken on, and this accounts for Kent’s later receipt of the note from Cordelia.

I have already suggested that original audiences, familiar with the earlier play King Leir, could readily have identified the character whom we will eventually know as Oswald (at this point in the Quarto he is Goneril’s unnamed gentleman) as Lear’s original Fool. They would have seen him as a young gentleman in the service of Leir who had been in the habit of coming into his presence disguised in the Fool’s motley. In Shakespeare’s play, this bungling gentleman enters twice upon Lear’s call for his Fool (which was the standard way of introducing new characters to the audience) and behaves in a very foolish manner, albeit at the behest of Goneril who encourages his negligence towards Lear with the words “If you come slack of former services”. I am maintaining that Oswald would have initially been identified as Skalliger from Leir who did let go the great wheel, Leir who was going downhill, and followed the great one, Gonorill, upwards in the opening scene of that play.

I know it must be hard to understand all this when you are coming from the standard understanding of the action of Lear. It took me a few years to see it! If you haven’t already read it, you could do nothing better towards a fuller understanding Lear than to read the earlier Leir which you can do by clicking the link in the margin here.

Shakespeare begins to make the situation appear increasingly dangerous for France and Cordelia to be in, presenting us with the almost immediate blow up between Goneril and Lear which leads Lear to determine to abandon her in favour of Regan. Clearly, Goneril is not going to give up the power that she has received from her father and any discovery of France and Cordelia on a mission to restore Lear to his throne will not meet with kindness! Lear has only been with Goneril a few days at the most and her earlier determination to “do something, and i’th’heat”, that is, immediately, and then that she “would ... breed occasions” that would cause Lear to hasten to her sister, has the desired effect.

Lear storms off after protesting that he would resume the kingly “shape” that Goneril might think he has cast off forever, but Fool lingers behind and is privy to the brief exchange between Goneril and Albany which shows the beginning disparity between them! Was this just idleness on the part of the Fool or was it a deliberate attempt to spy on Goneril? Given what I am seeing elsewhere in the text, I think the latter. There does not appear to be any other good reason for this delayed exit of the Fool.

Then we have Fool’s words in the aside, representing personal reflections:

A fox, when one has caught her

And such a daughter,

Should sure to the slaughter,

If my cap would buy a halter;

So the Fool follows after.

As we have already seen, here we have a fox, or a Fool, who is a daughter, a female, who will be hanged by a halter obtained in exchange for a Fool’s cap. This seems to be prophetic of Cordelia’s being hanged after she gives up her disguise as Lear’s Fool. If she were not Lear’s Fool, and was in fact ensconced in her French palace, she would not have even known about Kent’s disguised service. This female Fool is clearly concerned about the seriousness of the situation she sees developing around her. She sees that it could cost her her life!

I am maintaining that France disguises himself as a Servant in the Quarto, a disguise similar to that which worked for Kent. Perhaps this involved the removal of a French moustache and his borrowing other accents, in the same way that we hear that Kent has raz’d his likeness and borrowed other accents. In the Folio France disguises himself as a less open-faced Knight, a disguise which Edgar will adopt with success in the presence of his own brother later in the play. In the Quarto France will appear briefly as a knight also, but when Lear has the number of his riotous knights cut, France adopts the disguise of a Gentleman which he will use until he goes off to die in the bloody arbitrement.

In plays of that time Kings and Queens appeared as Gentlemen and Ladies on occasions. The Quarto stage directions for Goneril and Regan will later describe them as “two Ladies”. In other words, Goneril and Regan are not out there on the battlefield dressed up in their royal attire with crowns and all, even as France is not dressed as a King! That France should go through several disguises has its precedence or confirmation in the sub-plot where Edgar shifts through his several disguises of madman, seaside peasant and knight before returning to his true identity. In particular notice that Edgar’s appearance on stage as a knight would have been a complete surprise to the original audience. There is no advanced warning that he will so appear.

The second Act opens with further development of the troubles for Edgar in Lear’s sub-plot. This secondary plot strand, like other Shakespearean sub-plots, is included as a support for the main plot. So, as we have seen Lear almost self-deceived into undervaluing Cordelia as, “that little-seeming substance, or all of it, with our displeasure piec’d, and nothing more”, so now, Edmund successfully schemes to have the self-deluded Gloucestor reduce Edgar to the “nothing” he realizes he has become at the end of Act 2 Scene iii! As a consequence of the threat to his own life, Edgar disguises himself as poor Tom, and it is while in this disguise that he will eventually be pressed into leading his blinded father Gloucester towards Dover, but not before the Fool leads Lear in the same direction and then mysteriously disappears!

The disguised service rendered by Edgar towards his father who has abused him is certainly a high point in the morality of the play, and as it has been ordinarily understood, there is nothing in the main plot to equal, let alone surpass, this service rendered by an abused child to his or her own abusive father. The presence of this in the secondary plot should call for a like scenario in the main especially where a misunderstood, abused, and dispossessed daughter has hinted that she would “Love and be silent” and that what she well intended doing, she would do it before she spoke, and leave it to her father to make known what she had done.

Such an act of service would be higher on a scale of love than Edgar’s love, since Cordelia would have gone into disguise as Lear’s Fool in order to serve her abusive father, while Edgar goes into disguise as poor Tom to protect himself and later even protests that “Bad is the trade that must play fool to sorrow” as he is seconded to lead his father to Dover. It is because of his self-preserving disguise that he has to lead his father, whereas, in the main plot, I believe, Cordelia goes into disguise specifically in order that she may lead her father to safety.

Whether or not the Fool is Cordelia, the Fool is a real person in disguise, and we might compare this disguised person’s service with that of Kent who, in the main plot, has gone into disguise as a servant in order to seek to serve his master who has wrongfully banished him. There is a wonderful selflessness about the Fool whose whole intent is to labour to out-jest Lear’s heart-struck injuries. But while the Fool acts so totally selflessly it is very plain that Kent is serving with a view to being discovered, acknowledged and rewarded. And as wonderful as Kent’s service is, yet it is what Cornwall calls, his stubborn ancient knavery, and his being a “reverend braggart” that earns him a place in the stocks and is the thin edge of the wedge that opens what will be a chasm between Regan and her father outside Gloucester’s castle.

The clash between the two separate messengers to Regan, Oswald and Kent, could perhaps be compared with the opening of Romeo and Juliet where the clash between two servants opens wide the long-standing divide between the feuding Montague and Capulet families and brings about tragedy for Romeo and Juliet. Kent’s recognition of Oswald, his deriding him and challenging him to fight, causes such a commotion that Cornwall and Regan are ready to identify Kent as an example of Lear’s riotous knights of which Goneril has complained. Rather than paving the way to a friendly reception for Lear, Kent’s behaviour contributes to the rejection of Lear by his daughter before he gets anywhere near what he expected would be the comfort of Regan’s place. Lear never even sees Regan’s place.

The clash between Kent and Oswald gives us the longest description of any character in the play. Oswald is a “goodman boy” a “young master” who is “made” by a “tailor”, or less in quality than the cheap suit that he is wearing. He is an upstart “knave”, “knave”, “knave”, and Kent complains that Oswald smiles at Kent’s speeches as though he were a Fool! He is a knave and behaves like the motley Fool behaved towards Kent earlier. He is offered to us as both “knave” and “Fool” and I believe that the audience could have been expected in a few moments to see him as Lear’s original Fool who “runs away” leaving an opening for Cordelia as the motley Fool. Shakespeare has Kent protest that “no contraries hold more antipathy than I and such a knave”, and if, as I am maintaining, Oswald was to be identified with Skalliger who goes out of disguise and runs from the service of Leir, then he is the complete opposite of Kent who goes into disguise to regain admission into the service of Lear.

When Lear had earlier announced that he was off to Regan’s, the Fool seems to try to dissuade him from that path suggesting that he’d get no better reception there than he had at Goneril’s, perhaps hoping that Lear could be diverted right then and there to Dover to await the French forces who would come in and rout the British and restore him to his throne. The Fool had said “I can tell what I can tell” which echoed Cordelia’s words to her sisters in the opening of scene “I know you, what you are....” Cordelia and the early audiences of Lear could expect that some time about now, as in the source play Leir, Lear is going to be rejected be his second daughter and want to head off for France with his faithful servant Kent who has taken the place of Perillus.

Now in the beginning of Acts 2 Scene iv Lear arrives outside Gloucester’s castle in the company of the Fool and a Gentleman (Quarto has a less open-faced Knight instead of a Gentleman). If, as I maintain, the Fool is Cordelia’s disguised presence, then this Knight/Gentleman is France’s disguise. He has been accompanying Lear gathering intelligence about possible movements of the Duke and Queen. We see this in his comment to Lear, “As I learn’d, the night before there was no purpose in them of this remove.” The Fool voices the feeling that Gentleman will hear that “Winter’s not gone yet...” and then, a few moments later, after Lear leaves to talk with Regan, as if to try to further gauge the temperament of the Duke and Queen, the Gentleman asks Kent, “Made you no more offence but what you speak of?”

On the stage at this time are three people, Kent sitting on the ground in the stocks, the Knight/ Gentleman who is standing alongside the Fool questioning Kent. The Fool then says, “We’ll set thee to school to an ant, to teach thee...” which could suggest a combined effort here. The “we’ll” suggests that Fool and the Knight/Gentleman are working together. Earlier when the Servant/Knight is not present, Fool offers to teach Lear a speech saying, “Sirrah, I’ll teach thee a speech”, but here in the presence of the Knight/Gentleman it is “We’ll set thee to an ant, to teach thee....” Later, when this Gentleman meets Kent in the storm and is asked who is with Lear, the Gentleman will tell Kent that no one is with Lear except the Fool who is labouring to out-jest Lear’s heart-struck injuries, and it struck me that while the Gentleman had to be away from Lear at that time, yet he knows the Fool is sticking with Lear and he knows the reason for the Fool’s presence! They are working together for the good of Lear.

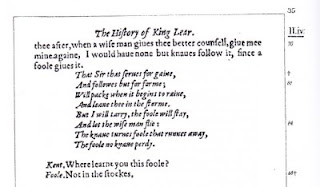

So after offering to set Kent to school to an ant, and stating the obvious about Lear’s situation, the Fool offers him advice, namely, “Let go thy hold when a great wheel runs down a hill, lest it break thy neck with following, but the great one that goes upward, let him draw thee after.”

In Lear we first learned that Lear had a Fool from the lips of Goneril who is annoyed that her gentleman (who we will eventually know as Oswald) had been struck by her father because he chided his Fool. We have already suggested that in the minds of the first audiences of Lear Oswald would have been identified with Skalliger who had been in the service of Leir but defected to the service of Gonorill. I am maintaining that Skalliger would have been in the habit of going into Leir’s presence disguised as his Fool, but when Skalliger leaves Leir for Gonorill, he ditches the motley which Cordelia then takes up in Lear.

We might ask why Oswald chided the Fool. Oswald had noticed that someone else was wearing his discarded motley and so chided this new Fool with words of advice that the Fool now repeats to Kent. Oswald was a wise man for having flown, but he is also a knave as Kent has found out! The Fool only wants knaves to use this advice, namely, leave the service of Lear, owning the advice given now as her own since she has been labelled both knave and Fool. She then lets us know that the knave turns out to be the Fool that ran away, and that she, the present Fool, is no knave, and neither is Kent, who through his time in the stocks is a Fool learning the folly of following Lear down the hill. Kent identifies with the notion of not running away and wonders where the Fool got this wisdom? It seems to me that by calling Kent “Fool” Cordelia is expressing her delight that Kent is on their side.

In the source play, Leir, and in Lear it is Oswald or his counterpart Skalliger who are singly depicted as forsaking Leir/Lear and as shifting and seeking his own personal gain. When asked, Oswald describes Lear as “My Lady’s father” and Lear calls him “my Lord’s knave” and then Oswald calls him “my Lord.” No one else has packed and left Lear in his storm. Oswald is the knave that turns out to be the Fool that has run away.

When Fool says, “But I will tarry, the Fool will stay” it seems to me that this is Cordelia speaking beneath her disguise in the same way as I believe she spoke earlier while reflecting on Lear’s giving away his crown saying, “If I speak like myself in this let him be whipp’d that first finds it so” because she has given away her British crown and could be wearing her French one.

Cordelia is protesting that she is not a knave though she is the Fool. The knave was the Fool who ran from the service of Leir that Kent has just encountered outside Gloucester’s castle and declared him so to be. She is no knave and neither is Kent. They are both foolish for following Lear downhill!

If there is another explanation for this section of the play, I would like to see it.

I believe that France and Cordelia hope to team up with Kent to bring Lear down to Dover from where they can be protected by the invading French army, and advance against the British forces, defeating them and restoring Lear as happened in the source play Leir. But Kent doesn’t see Cordelia nor does he see France! Kent thinks that he alone is capable of going into disguise to serve Lear, and virtually everyone has accepted that this is the case because they have ignored what Cordelia and France said in the opening scene!

Act 3 opens with Kent and this Gentleman, whom I believe is France in disguise, meeting up away from Lear’s presence out in the storm. It seems to me that the Gentleman has left Lear in the care of the Fool and gone off to check with his subordinates about the progress his army is making towards the shores of Dover. The foulest winter storm has not long begun with lightning and thunder.

Kent however is not so gainfully employed. He is out with a letter he has written to Cordelia telling her of his disguised service of her father. He is looking for a way to get this letter to her in the hope that she will read it and think highly of him. He expects that she has just arrived with the French army, and he offers this Gentleman the opportunity to advance his standing, “build so far” on his credit, by delivering the letter to her.

The conversation between the Gentleman and Kent in this scene is a telling one, for it begins by Kent essentially asking the Gentleman's identity, but receiving the non-committal answer - "One minded like the weather most unquietly." It seems that the Gentleman wished to remain anonymous. His response can be compared with the response the disguised Kent gave to Lear when he takes him on as a servant. Kent did not reveal his name to Lear. He was simply identified himself as “a man.”

Despite this being the first time the speech prefix "Gent." appears in the Quarto, Kent says, "I know you", and again "I do know you", which would suggest that the Gentleman has been on stage before, and that the audience could have recognised him, in the same way that Kent, told Oswald, whom the audience has already met, that he knew him. There’s no reason to believe that this Gentleman is any different to the Folio’s Gentleman we’ve seen earlier for Kent expects the Gentleman to know the whereabouts of Lear. Kent's question, "Where’s the King?" could have afforded great irony if the audience had perceived that Kent is talking to a king (France) who he says he knows, but obviously doesn't!

In the conversation between Kent and the Gentleman, Kent speaks of the "secret feet in some of our best Ports". The Folio at this point speaks of these secret feet as being

... to France the spies and speculations

Intelligent of our State. What hath been seen,

Either in snuffs and packings of the Dukes,

Or the hard rein which both of them have borne

Against the old kind King; or something deeper,

Whereof perchance these are but furnishings –

and then he leaves off.

If these "secret feet" appear in the play, this Gentleman, who has been observing, questioning and reporting things about the opposition, surely has two of them.

I realise that Shakespeare's characterisation of Kent here is not what most have understood it to be, and we will have more to say about this later. But what we have here, I believe, is Kent telling the King of France, whose identity he says he knows, but doesn't know, that the King of France has his spies in Britain, and goodness only knows what they’ve seen!

He offers to lend France credit on which he can build his reputation, which is exactly what Kent is trying to do! Kent seeks to assure France that he will see Cordelia and gives him his purse containing his ring which he is to give to her! The association of rings and purses with disguise is everywhere in Shakespeare. We have a classic example of this in The Merchant of Venice, which King James had seen twice not many months before watching King Lear, where Bassanio and Gratiano give away their wedding rings inadvertently to their disguised wives. In the secondary plot of Lear the blind Gloucester will soon give two purses, one containing a ring, to his disguised son. All of this is the height of dramatic irony, and so Shakespearean!

Kent is depicted as confiding in this Gentleman, telling him that there is division between Albany and Cornwall “although as yet the face of it is covered with mutual cunning”. “Mutual cunning” might or might not be the best description of the differences between Albany and Cornwall, but this description of their relationship could be seen to reflect on the relationship between Kent and this Gentleman, France, for there is something like "mutual cunning", in a good cause, covering the faces of Kent and France. Kent's cunning is not as artful as France's because obviously France knows who Kent is, but Kent thinks he has one up on this Gentleman but doesn't! The lofty language of the Gentleman here is consistent with that of the Servant/Knight we’ve seen earlier and he is concerned, as always, to focus on the needs of Lear and the mission of the Fool, who he knows is labouring to "out-jest” Lear's “heart-strook injuries." The Gentleman has his eye on Lear, his father-in-law, and on the Fool, his wife. This is wonderful drama!

Kent seems only to be concerned to get the record of his service of Lear to Cordelia, and the Gentleman is perplexed that Kent has no more to say. Kent is suddenly conscious that he should be looking after Lear who is only being cared for by the Fool and so before he goes off to try to find Lear, he enlists the Gentleman in the search for him suggesting that whoever finds him first should call for the other. When in the next scene Kent comes upon Lear he completely ignores the Fool and doesn’t seem to be worried about calling for the Gentleman as he had undertaken to do.

For the moment I would like to skip over the storm scene, the hovel and the disappearance of the Fool and pick up where we find this Gentleman talking again with Kent.

Act 4 Scene iii opens with the French having landed at Dover and set up camp. Kent has wandered away from Lear again and met up with this same Gentleman enquiring about the way Cordelia had received the letters he had given this Gentleman for her.

Kent must have asked where the King of France is and he has been told that the King has gone back to France. Kent asked about the return of the king no doubt because he was looking for some sort of recognition of his service of Lear from the King of France. This I take to be the case from his question concerning Cordelia's reading and reacting to his letter, "Was this before the King returned?" He is essentially asking if the King of France could have heard what he had done. Of course he would deny any interest in recognition; he will later tell Cordelia that “to be acknowledged” “is over-paid”!

The scene opens with Kent's asking the King of France why the King of France had to go back! There is dramatic irony in his asking France, "know you no reason?" France comes up with a vague statement which hardly would be sufficient reason for him to leave the woman he loves in a situation of danger, and go against his earlier assertion that "Love's not love, when it is mingled with regards that stand aloof from th'entire point."

To Kent's question about whom the King of France left as General in charge of the French forces, the answer comes back, "Monsieur La Far." This is France having a go at Kent! In Love's Labour's Lost we have someone being called "Monsieur the nice" which has an obvious meaning. Zinevra, of Baccassio's The Decameron, who lies behind the character of Cymbeline’s Imogen, takes on the disguised name "Sicurano da Finale", which can be roughly translated secure at last, expressive of her feeling of security. "Monsieur le Fer", the name of the French Soldier in King Henry V is clearly chosen for Pistol to respond to with "I'll fer him, and firk him, and ferret him...." Here in Lear "Monsieur La Far" suggests someone who is afar off as opposed to standing in his presence, and is France's way of playing with Kent who still does not recognise him, in the same way as the disguised Vincentio plays with Lucio in Measure for Measure. The description of Cordelia's ripe lip which, "seem not to know, what guests were in her eyes" would, perhaps, be meant to reflect on Kent's not knowing what guest (France) was in his eyes - "seem" is present tense.

In this scene we find that the Gentleman continues to be in touch with the movements of the British forces. To Kent’s “Of Albany’s and Cornwall’s powers you heard not?” the Gentleman responds “’Tis so they are afoot.”

There is dramatic irony when Shakespeare has Kent tell France that some dear cause will wrap him up in concealment for a while longer, but when it is known who he really is, the Gentleman will not be sorry, but feel justified for having helped him, an Earl. But the real situation is that the King of France is lending an Earl his acquaintance, and the Earl doesn't know it!

A little over half way through Act 4 Scene vi this Gentleman finds Lear roaming around the countryside and assures him of his rescue. His first words to Lear, "Sir, your most dear daughter ----" echo France’s description of Cordelia at the beginning of Lear "The best, the dearest...", and corresponds with the King of France's words to Leir, at the reunion of Leir and Cordella, "she is your loving daughter". Lear's request for surgeons leads the Gentleman to say, "You shall have any thing" which was the attitude of the King of France towards Leir in the 1605 version where he tells Leir “Thank heavens, not me, my zeal to you is such, command my utmost, I will never grudge.”

To Lear's excited realization "I am a king, masters, know you that?" the Gentleman says, "You are a royal one and we obey you", which might have been meant to reflect the King of France's words to Leir in the 1605 version "she is your loving daughter and honours you with a respectful duty, as if you were the Monarch of the world.”

The Gentleman, France, says of Cordelia "Thou hast one daughter who redeems nature from the general curse". This description could remind one of Lear’s earlier "Yet I have left a daughter" and "I have another daughter." Lear meant Regan in both instances, of course, but since we knew she would treat him the same as Goneril had, we might have thought of Cordelia, and might have seen her in the motley. One might reasonably ask what Cordelia had done to this point to redeem nature from the general curse if she had not been the Fool striving to out-jest Lear's heart-struck injuries and lead him towards Dover and safety.

The conversation between Edgar and this Gentleman shows Edgar paying respect to this Gentleman with, "Hail, gentle sir" and asking "Do you hear aught, sir, of a battle toward?" This is somewhat like Perdita's respectful welcome of the disguised Polixines and Camillo, and the way they address her as "gentle maiden" in The Winter’s Tale. There is recognition of a noble quality in the Gentleman in the words of Edgar. The Gentleman again shows he is very much aware what is going on with respect to the battle. He knows the British army is near and the French are expecting to see them any hour. One could argue that an ordinary gentleman might possibly not be as confident in these matters as this one seems to be, but the King of France would certainly be very well informed. He knows that the French army has moved on from Dover while the Queen is still there “on special cause”.

I have already written about France’s going off to die in the battle in my earlier post. I have much more that I want to post here in support of my understanding that Cordelia and France never left England but stayed and served Lear in disguise.

To express an interest in receiving notice of the next posting please either follow my Twitter tweets @auusa or follow this blog. If you have any comments you wish to make, please do not hesitate to do so either below or via Twitter. I am more than willing to receive your critiques. Again, I am sorry if there is a bit of repetition in my posts, but I find it hard to make it understandable without repetition.

A day or so after recent operations in Abbottabad, Pakistan, we heard of a nearby safe house that had been the hideout for CIA operatives for several months in advance of the attack. From there these spies were able to gather intelligence observing the comings and goings in and around the building that proved to be significant.

It’s always exciting to me to wonder how these spies are able to pull off their successful missions all without being detected. They must have been seen by many of the locals so I wonder at the disguises they adopted, their skills in foreign languages and their ability to makeshift in foreign locations. Thinking about this also makes me wonder what safe houses or intelligence gathering missions are currently in operation in trouble spots around the world that could one day pay off or be busted.

It’s always exciting to me to wonder how these spies are able to pull off their successful missions all without being detected. They must have been seen by many of the locals so I wonder at the disguises they adopted, their skills in foreign languages and their ability to makeshift in foreign locations. Thinking about this also makes me wonder what safe houses or intelligence gathering missions are currently in operation in trouble spots around the world that could one day pay off or be busted.

There was a case of French “intelligence operatives” on British soil that seems to have been completely overlooked! Even though it was a fictional one there has been little or no attention given to it in 400 years, and yet millions of people have read about it in the pages of Shakespeare’s King Lear most without realizing what happened!

To many people King Lear is such a boring play! Today’s theatre-goers have a keen appetite for the loud and mournful speeches of the king “more sinned against than sinning” and performances seem to be judged by how well a lead actor does in delivering these. But there is so much more in King Lear that is so exciting that people are completely missing.

If you have been following my blog you will know that I am referring to the presence of the King of France and Cordelia on British soil. They are there disguised as a Servant/Knight and Gentleman and as Lear’s Fool.

In my earlier posts I showed good reasons for believing that France and Cordelia never left Britain, but stayed behind and served Lear attempting to direct him towards Dover where France had ordered his troops to land in the hope of restoring Lear to his throne.

How exciting is this?! A foreign king and a banished princess, France and Cordelia, gathering intelligence about movements of Queens, possible divisions between dukes, strength of military power, and trying to get those loyal to Lear, Kent and Gloucester, to help in directing the aged king towards Dover and to the safety of armed French forces. All this without being detected, for that would have been dangerous! Indeed, all of this without wanting to be even acknowledged for their bravery and service.

This is what Shakespeare has presented to us, and their cunning, covert operations have been completely overlooked for 400 years! However, the record is all there waiting to be rediscovered in the words, speech prefixes, stage directions, textual emendations, Biblical allusions, as well as evident glances at the sources of Shakespeare’s play.

I have already drawn attention to Cordelia’s getting her note to Kent whose disguise and whereabouts she could not have known unless she were the Fool. Cordelia had heard Kent’s obscure words, “He’ll shape his old course in a country new” and the Fool was there moments after Lear had failed to see through Kent’s disguise as a servant and accepted the one he had banished from the land into his personal service again.

I am maintaining that France was there too, disguised as a Servant (in the Quarto) and a Knight (in the Folio), preparing the way for the entry of the Fool by mouthing what everyone believed, that “my young lady”, Cordelia, had gone “into France”. When the Fool finally arrives on the stage for the first time, the first thing the Fool does is to chide Kent for “taking one's part that's out of favour” and then expresses the reversal of Lear’s assumed action saying of him, “this fellow has banished two of's daughters, and did the third a blessing against his will....”

Because Lear and everyone else believes that Cordelia has gone to France, she has found a way to fulfil that which she said that she would have wanted. Before leaving her sisters on the day of the division of the kingdom, she had committed her father to her sisters’ “professed bosoms”, however she wished she could “prefer him to a better place” namely her own bosom, or to what Lear referred to as “her kind nursery.” If Cordelia were in France, it would not have been “against his will.” By reversing the states of Goneril and Regan from Lear’s loving hostesses to “banished” the Fool reverses Cordelia’s state from banished to not banished and present somewhere in disguise!

There is no doubt in my mind that this shows that the Fool, Cordelia, sees through the disguise that Kent has taken on, and this accounts for Kent’s later receipt of the note from Cordelia.

I have already suggested that original audiences, familiar with the earlier play King Leir, could readily have identified the character whom we will eventually know as Oswald (at this point in the Quarto he is Goneril’s unnamed gentleman) as Lear’s original Fool. They would have seen him as a young gentleman in the service of Leir who had been in the habit of coming into his presence disguised in the Fool’s motley. In Shakespeare’s play, this bungling gentleman enters twice upon Lear’s call for his Fool (which was the standard way of introducing new characters to the audience) and behaves in a very foolish manner, albeit at the behest of Goneril who encourages his negligence towards Lear with the words “If you come slack of former services”. I am maintaining that Oswald would have initially been identified as Skalliger from Leir who did let go the great wheel, Leir who was going downhill, and followed the great one, Gonorill, upwards in the opening scene of that play.

I know it must be hard to understand all this when you are coming from the standard understanding of the action of Lear. It took me a few years to see it! If you haven’t already read it, you could do nothing better towards a fuller understanding Lear than to read the earlier Leir which you can do by clicking the link in the margin here.

Shakespeare begins to make the situation appear increasingly dangerous for France and Cordelia to be in, presenting us with the almost immediate blow up between Goneril and Lear which leads Lear to determine to abandon her in favour of Regan. Clearly, Goneril is not going to give up the power that she has received from her father and any discovery of France and Cordelia on a mission to restore Lear to his throne will not meet with kindness! Lear has only been with Goneril a few days at the most and her earlier determination to “do something, and i’th’heat”, that is, immediately, and then that she “would ... breed occasions” that would cause Lear to hasten to her sister, has the desired effect.

Lear storms off after protesting that he would resume the kingly “shape” that Goneril might think he has cast off forever, but Fool lingers behind and is privy to the brief exchange between Goneril and Albany which shows the beginning disparity between them! Was this just idleness on the part of the Fool or was it a deliberate attempt to spy on Goneril? Given what I am seeing elsewhere in the text, I think the latter. There does not appear to be any other good reason for this delayed exit of the Fool.

Then we have Fool’s words in the aside, representing personal reflections:

A fox, when one has caught her

And such a daughter,

Should sure to the slaughter,

If my cap would buy a halter;

So the Fool follows after.

As we have already seen, here we have a fox, or a Fool, who is a daughter, a female, who will be hanged by a halter obtained in exchange for a Fool’s cap. This seems to be prophetic of Cordelia’s being hanged after she gives up her disguise as Lear’s Fool. If she were not Lear’s Fool, and was in fact ensconced in her French palace, she would not have even known about Kent’s disguised service. This female Fool is clearly concerned about the seriousness of the situation she sees developing around her. She sees that it could cost her her life!

I am maintaining that France disguises himself as a Servant in the Quarto, a disguise similar to that which worked for Kent. Perhaps this involved the removal of a French moustache and his borrowing other accents, in the same way that we hear that Kent has raz’d his likeness and borrowed other accents. In the Folio France disguises himself as a less open-faced Knight, a disguise which Edgar will adopt with success in the presence of his own brother later in the play. In the Quarto France will appear briefly as a knight also, but when Lear has the number of his riotous knights cut, France adopts the disguise of a Gentleman which he will use until he goes off to die in the bloody arbitrement.

In plays of that time Kings and Queens appeared as Gentlemen and Ladies on occasions. The Quarto stage directions for Goneril and Regan will later describe them as “two Ladies”. In other words, Goneril and Regan are not out there on the battlefield dressed up in their royal attire with crowns and all, even as France is not dressed as a King! That France should go through several disguises has its precedence or confirmation in the sub-plot where Edgar shifts through his several disguises of madman, seaside peasant and knight before returning to his true identity. In particular notice that Edgar’s appearance on stage as a knight would have been a complete surprise to the original audience. There is no advanced warning that he will so appear.

The second Act opens with further development of the troubles for Edgar in Lear’s sub-plot. This secondary plot strand, like other Shakespearean sub-plots, is included as a support for the main plot. So, as we have seen Lear almost self-deceived into undervaluing Cordelia as, “that little-seeming substance, or all of it, with our displeasure piec’d, and nothing more”, so now, Edmund successfully schemes to have the self-deluded Gloucestor reduce Edgar to the “nothing” he realizes he has become at the end of Act 2 Scene iii! As a consequence of the threat to his own life, Edgar disguises himself as poor Tom, and it is while in this disguise that he will eventually be pressed into leading his blinded father Gloucester towards Dover, but not before the Fool leads Lear in the same direction and then mysteriously disappears!

The disguised service rendered by Edgar towards his father who has abused him is certainly a high point in the morality of the play, and as it has been ordinarily understood, there is nothing in the main plot to equal, let alone surpass, this service rendered by an abused child to his or her own abusive father. The presence of this in the secondary plot should call for a like scenario in the main especially where a misunderstood, abused, and dispossessed daughter has hinted that she would “Love and be silent” and that what she well intended doing, she would do it before she spoke, and leave it to her father to make known what she had done.

Such an act of service would be higher on a scale of love than Edgar’s love, since Cordelia would have gone into disguise as Lear’s Fool in order to serve her abusive father, while Edgar goes into disguise as poor Tom to protect himself and later even protests that “Bad is the trade that must play fool to sorrow” as he is seconded to lead his father to Dover. It is because of his self-preserving disguise that he has to lead his father, whereas, in the main plot, I believe, Cordelia goes into disguise specifically in order that she may lead her father to safety.

Whether or not the Fool is Cordelia, the Fool is a real person in disguise, and we might compare this disguised person’s service with that of Kent who, in the main plot, has gone into disguise as a servant in order to seek to serve his master who has wrongfully banished him. There is a wonderful selflessness about the Fool whose whole intent is to labour to out-jest Lear’s heart-struck injuries. But while the Fool acts so totally selflessly it is very plain that Kent is serving with a view to being discovered, acknowledged and rewarded. And as wonderful as Kent’s service is, yet it is what Cornwall calls, his stubborn ancient knavery, and his being a “reverend braggart” that earns him a place in the stocks and is the thin edge of the wedge that opens what will be a chasm between Regan and her father outside Gloucester’s castle.

The clash between the two separate messengers to Regan, Oswald and Kent, could perhaps be compared with the opening of Romeo and Juliet where the clash between two servants opens wide the long-standing divide between the feuding Montague and Capulet families and brings about tragedy for Romeo and Juliet. Kent’s recognition of Oswald, his deriding him and challenging him to fight, causes such a commotion that Cornwall and Regan are ready to identify Kent as an example of Lear’s riotous knights of which Goneril has complained. Rather than paving the way to a friendly reception for Lear, Kent’s behaviour contributes to the rejection of Lear by his daughter before he gets anywhere near what he expected would be the comfort of Regan’s place. Lear never even sees Regan’s place.

The clash between Kent and Oswald gives us the longest description of any character in the play. Oswald is a “goodman boy” a “young master” who is “made” by a “tailor”, or less in quality than the cheap suit that he is wearing. He is an upstart “knave”, “knave”, “knave”, and Kent complains that Oswald smiles at Kent’s speeches as though he were a Fool! He is a knave and behaves like the motley Fool behaved towards Kent earlier. He is offered to us as both “knave” and “Fool” and I believe that the audience could have been expected in a few moments to see him as Lear’s original Fool who “runs away” leaving an opening for Cordelia as the motley Fool. Shakespeare has Kent protest that “no contraries hold more antipathy than I and such a knave”, and if, as I am maintaining, Oswald was to be identified with Skalliger who goes out of disguise and runs from the service of Leir, then he is the complete opposite of Kent who goes into disguise to regain admission into the service of Lear.

When Lear had earlier announced that he was off to Regan’s, the Fool seems to try to dissuade him from that path suggesting that he’d get no better reception there than he had at Goneril’s, perhaps hoping that Lear could be diverted right then and there to Dover to await the French forces who would come in and rout the British and restore him to his throne. The Fool had said “I can tell what I can tell” which echoed Cordelia’s words to her sisters in the opening of scene “I know you, what you are....” Cordelia and the early audiences of Lear could expect that some time about now, as in the source play Leir, Lear is going to be rejected be his second daughter and want to head off for France with his faithful servant Kent who has taken the place of Perillus.

Now in the beginning of Acts 2 Scene iv Lear arrives outside Gloucester’s castle in the company of the Fool and a Gentleman (Quarto has a less open-faced Knight instead of a Gentleman). If, as I maintain, the Fool is Cordelia’s disguised presence, then this Knight/Gentleman is France’s disguise. He has been accompanying Lear gathering intelligence about possible movements of the Duke and Queen. We see this in his comment to Lear, “As I learn’d, the night before there was no purpose in them of this remove.” The Fool voices the feeling that Gentleman will hear that “Winter’s not gone yet...” and then, a few moments later, after Lear leaves to talk with Regan, as if to try to further gauge the temperament of the Duke and Queen, the Gentleman asks Kent, “Made you no more offence but what you speak of?”

On the stage at this time are three people, Kent sitting on the ground in the stocks, the Knight/ Gentleman who is standing alongside the Fool questioning Kent. The Fool then says, “We’ll set thee to school to an ant, to teach thee...” which could suggest a combined effort here. The “we’ll” suggests that Fool and the Knight/Gentleman are working together. Earlier when the Servant/Knight is not present, Fool offers to teach Lear a speech saying, “Sirrah, I’ll teach thee a speech”, but here in the presence of the Knight/Gentleman it is “We’ll set thee to an ant, to teach thee....” Later, when this Gentleman meets Kent in the storm and is asked who is with Lear, the Gentleman will tell Kent that no one is with Lear except the Fool who is labouring to out-jest Lear’s heart-struck injuries, and it struck me that while the Gentleman had to be away from Lear at that time, yet he knows the Fool is sticking with Lear and he knows the reason for the Fool’s presence! They are working together for the good of Lear.

So after offering to set Kent to school to an ant, and stating the obvious about Lear’s situation, the Fool offers him advice, namely, “Let go thy hold when a great wheel runs down a hill, lest it break thy neck with following, but the great one that goes upward, let him draw thee after.”

In Lear we first learned that Lear had a Fool from the lips of Goneril who is annoyed that her gentleman (who we will eventually know as Oswald) had been struck by her father because he chided his Fool. We have already suggested that in the minds of the first audiences of Lear Oswald would have been identified with Skalliger who had been in the service of Leir but defected to the service of Gonorill. I am maintaining that Skalliger would have been in the habit of going into Leir’s presence disguised as his Fool, but when Skalliger leaves Leir for Gonorill, he ditches the motley which Cordelia then takes up in Lear.

We might ask why Oswald chided the Fool. Oswald had noticed that someone else was wearing his discarded motley and so chided this new Fool with words of advice that the Fool now repeats to Kent. Oswald was a wise man for having flown, but he is also a knave as Kent has found out! The Fool only wants knaves to use this advice, namely, leave the service of Lear, owning the advice given now as her own since she has been labelled both knave and Fool. She then lets us know that the knave turns out to be the Fool that ran away, and that she, the present Fool, is no knave, and neither is Kent, who through his time in the stocks is a Fool learning the folly of following Lear down the hill. Kent identifies with the notion of not running away and wonders where the Fool got this wisdom? It seems to me that by calling Kent “Fool” Cordelia is expressing her delight that Kent is on their side.

In the source play, Leir, and in Lear it is Oswald or his counterpart Skalliger who are singly depicted as forsaking Leir/Lear and as shifting and seeking his own personal gain. When asked, Oswald describes Lear as “My Lady’s father” and Lear calls him “my Lord’s knave” and then Oswald calls him “my Lord.” No one else has packed and left Lear in his storm. Oswald is the knave that turns out to be the Fool that has run away.

When Fool says, “But I will tarry, the Fool will stay” it seems to me that this is Cordelia speaking beneath her disguise in the same way as I believe she spoke earlier while reflecting on Lear’s giving away his crown saying, “If I speak like myself in this let him be whipp’d that first finds it so” because she has given away her British crown and could be wearing her French one.

Cordelia is protesting that she is not a knave though she is the Fool. The knave was the Fool who ran from the service of Leir that Kent has just encountered outside Gloucester’s castle and declared him so to be. She is no knave and neither is Kent. They are both foolish for following Lear downhill!

If there is another explanation for this section of the play, I would like to see it.

I believe that France and Cordelia hope to team up with Kent to bring Lear down to Dover from where they can be protected by the invading French army, and advance against the British forces, defeating them and restoring Lear as happened in the source play Leir. But Kent doesn’t see Cordelia nor does he see France! Kent thinks that he alone is capable of going into disguise to serve Lear, and virtually everyone has accepted that this is the case because they have ignored what Cordelia and France said in the opening scene!

Act 3 opens with Kent and this Gentleman, whom I believe is France in disguise, meeting up away from Lear’s presence out in the storm. It seems to me that the Gentleman has left Lear in the care of the Fool and gone off to check with his subordinates about the progress his army is making towards the shores of Dover. The foulest winter storm has not long begun with lightning and thunder.

Kent however is not so gainfully employed. He is out with a letter he has written to Cordelia telling her of his disguised service of her father. He is looking for a way to get this letter to her in the hope that she will read it and think highly of him. He expects that she has just arrived with the French army, and he offers this Gentleman the opportunity to advance his standing, “build so far” on his credit, by delivering the letter to her.

The conversation between the Gentleman and Kent in this scene is a telling one, for it begins by Kent essentially asking the Gentleman's identity, but receiving the non-committal answer - "One minded like the weather most unquietly." It seems that the Gentleman wished to remain anonymous. His response can be compared with the response the disguised Kent gave to Lear when he takes him on as a servant. Kent did not reveal his name to Lear. He was simply identified himself as “a man.”

Despite this being the first time the speech prefix "Gent." appears in the Quarto, Kent says, "I know you", and again "I do know you", which would suggest that the Gentleman has been on stage before, and that the audience could have recognised him, in the same way that Kent, told Oswald, whom the audience has already met, that he knew him. There’s no reason to believe that this Gentleman is any different to the Folio’s Gentleman we’ve seen earlier for Kent expects the Gentleman to know the whereabouts of Lear. Kent's question, "Where’s the King?" could have afforded great irony if the audience had perceived that Kent is talking to a king (France) who he says he knows, but obviously doesn't!

In the conversation between Kent and the Gentleman, Kent speaks of the "secret feet in some of our best Ports". The Folio at this point speaks of these secret feet as being

... to France the spies and speculations

Intelligent of our State. What hath been seen,

Either in snuffs and packings of the Dukes,

Or the hard rein which both of them have borne

Against the old kind King; or something deeper,

Whereof perchance these are but furnishings –

and then he leaves off.

If these "secret feet" appear in the play, this Gentleman, who has been observing, questioning and reporting things about the opposition, surely has two of them.

I realise that Shakespeare's characterisation of Kent here is not what most have understood it to be, and we will have more to say about this later. But what we have here, I believe, is Kent telling the King of France, whose identity he says he knows, but doesn't know, that the King of France has his spies in Britain, and goodness only knows what they’ve seen!

He offers to lend France credit on which he can build his reputation, which is exactly what Kent is trying to do! Kent seeks to assure France that he will see Cordelia and gives him his purse containing his ring which he is to give to her! The association of rings and purses with disguise is everywhere in Shakespeare. We have a classic example of this in The Merchant of Venice, which King James had seen twice not many months before watching King Lear, where Bassanio and Gratiano give away their wedding rings inadvertently to their disguised wives. In the secondary plot of Lear the blind Gloucester will soon give two purses, one containing a ring, to his disguised son. All of this is the height of dramatic irony, and so Shakespearean!

Kent is depicted as confiding in this Gentleman, telling him that there is division between Albany and Cornwall “although as yet the face of it is covered with mutual cunning”. “Mutual cunning” might or might not be the best description of the differences between Albany and Cornwall, but this description of their relationship could be seen to reflect on the relationship between Kent and this Gentleman, France, for there is something like "mutual cunning", in a good cause, covering the faces of Kent and France. Kent's cunning is not as artful as France's because obviously France knows who Kent is, but Kent thinks he has one up on this Gentleman but doesn't! The lofty language of the Gentleman here is consistent with that of the Servant/Knight we’ve seen earlier and he is concerned, as always, to focus on the needs of Lear and the mission of the Fool, who he knows is labouring to "out-jest” Lear's “heart-strook injuries." The Gentleman has his eye on Lear, his father-in-law, and on the Fool, his wife. This is wonderful drama!

Kent seems only to be concerned to get the record of his service of Lear to Cordelia, and the Gentleman is perplexed that Kent has no more to say. Kent is suddenly conscious that he should be looking after Lear who is only being cared for by the Fool and so before he goes off to try to find Lear, he enlists the Gentleman in the search for him suggesting that whoever finds him first should call for the other. When in the next scene Kent comes upon Lear he completely ignores the Fool and doesn’t seem to be worried about calling for the Gentleman as he had undertaken to do.

For the moment I would like to skip over the storm scene, the hovel and the disappearance of the Fool and pick up where we find this Gentleman talking again with Kent.

Act 4 Scene iii opens with the French having landed at Dover and set up camp. Kent has wandered away from Lear again and met up with this same Gentleman enquiring about the way Cordelia had received the letters he had given this Gentleman for her.

Kent must have asked where the King of France is and he has been told that the King has gone back to France. Kent asked about the return of the king no doubt because he was looking for some sort of recognition of his service of Lear from the King of France. This I take to be the case from his question concerning Cordelia's reading and reacting to his letter, "Was this before the King returned?" He is essentially asking if the King of France could have heard what he had done. Of course he would deny any interest in recognition; he will later tell Cordelia that “to be acknowledged” “is over-paid”!

The scene opens with Kent's asking the King of France why the King of France had to go back! There is dramatic irony in his asking France, "know you no reason?" France comes up with a vague statement which hardly would be sufficient reason for him to leave the woman he loves in a situation of danger, and go against his earlier assertion that "Love's not love, when it is mingled with regards that stand aloof from th'entire point."

To Kent's question about whom the King of France left as General in charge of the French forces, the answer comes back, "Monsieur La Far." This is France having a go at Kent! In Love's Labour's Lost we have someone being called "Monsieur the nice" which has an obvious meaning. Zinevra, of Baccassio's The Decameron, who lies behind the character of Cymbeline’s Imogen, takes on the disguised name "Sicurano da Finale", which can be roughly translated secure at last, expressive of her feeling of security. "Monsieur le Fer", the name of the French Soldier in King Henry V is clearly chosen for Pistol to respond to with "I'll fer him, and firk him, and ferret him...." Here in Lear "Monsieur La Far" suggests someone who is afar off as opposed to standing in his presence, and is France's way of playing with Kent who still does not recognise him, in the same way as the disguised Vincentio plays with Lucio in Measure for Measure. The description of Cordelia's ripe lip which, "seem not to know, what guests were in her eyes" would, perhaps, be meant to reflect on Kent's not knowing what guest (France) was in his eyes - "seem" is present tense.

In this scene we find that the Gentleman continues to be in touch with the movements of the British forces. To Kent’s “Of Albany’s and Cornwall’s powers you heard not?” the Gentleman responds “’Tis so they are afoot.”

There is dramatic irony when Shakespeare has Kent tell France that some dear cause will wrap him up in concealment for a while longer, but when it is known who he really is, the Gentleman will not be sorry, but feel justified for having helped him, an Earl. But the real situation is that the King of France is lending an Earl his acquaintance, and the Earl doesn't know it!

A little over half way through Act 4 Scene vi this Gentleman finds Lear roaming around the countryside and assures him of his rescue. His first words to Lear, "Sir, your most dear daughter ----" echo France’s description of Cordelia at the beginning of Lear "The best, the dearest...", and corresponds with the King of France's words to Leir, at the reunion of Leir and Cordella, "she is your loving daughter". Lear's request for surgeons leads the Gentleman to say, "You shall have any thing" which was the attitude of the King of France towards Leir in the 1605 version where he tells Leir “Thank heavens, not me, my zeal to you is such, command my utmost, I will never grudge.”

To Lear's excited realization "I am a king, masters, know you that?" the Gentleman says, "You are a royal one and we obey you", which might have been meant to reflect the King of France's words to Leir in the 1605 version "she is your loving daughter and honours you with a respectful duty, as if you were the Monarch of the world.”

The Gentleman, France, says of Cordelia "Thou hast one daughter who redeems nature from the general curse". This description could remind one of Lear’s earlier "Yet I have left a daughter" and "I have another daughter." Lear meant Regan in both instances, of course, but since we knew she would treat him the same as Goneril had, we might have thought of Cordelia, and might have seen her in the motley. One might reasonably ask what Cordelia had done to this point to redeem nature from the general curse if she had not been the Fool striving to out-jest Lear's heart-struck injuries and lead him towards Dover and safety.

The conversation between Edgar and this Gentleman shows Edgar paying respect to this Gentleman with, "Hail, gentle sir" and asking "Do you hear aught, sir, of a battle toward?" This is somewhat like Perdita's respectful welcome of the disguised Polixines and Camillo, and the way they address her as "gentle maiden" in The Winter’s Tale. There is recognition of a noble quality in the Gentleman in the words of Edgar. The Gentleman again shows he is very much aware what is going on with respect to the battle. He knows the British army is near and the French are expecting to see them any hour. One could argue that an ordinary gentleman might possibly not be as confident in these matters as this one seems to be, but the King of France would certainly be very well informed. He knows that the French army has moved on from Dover while the Queen is still there “on special cause”.

I have already written about France’s going off to die in the battle in my earlier post. I have much more that I want to post here in support of my understanding that Cordelia and France never left England but stayed and served Lear in disguise.

To express an interest in receiving notice of the next posting please either follow my Twitter tweets @auusa or follow this blog. If you have any comments you wish to make, please do not hesitate to do so either below or via Twitter. I am more than willing to receive your critiques. Again, I am sorry if there is a bit of repetition in my posts, but I find it hard to make it understandable without repetition.